|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In this column we examine an exciting part of medieval history: | |

|

The only period example (I can think of) of a king killed by a paid, professional assassin! |

|

The destruction of a twelve hundred year old empire! |

|

The holy city of Jerusalem placed under Interdict! |

|

Religiously inspired cannibalism! |

| Yes, that's right, we're covering the Crusades. They're a lot more than just Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. | |

|

The First Crusade 1095-99 In 1095, the Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus appealed to Pope Urban II in Rome for help against the Seljuk Turks. The Seljuks had been encroaching on Byzantine territories for decades, and Alexius wanted military aid - presumably a couple of companies of knights or mercenaries, or something like that. Instead, for reasons of his own, Pope Urban made it a religious quest for all western Christendom, to conquer the Holy Land and the city of Jerusalem from the infidel. The great mass of "pilgrims in arms" got underway in 1096. There was no overall organization or command, more an off-and-on consensus among leaders of various regional/national groups: Raymond of Toulouse and the papal legate, Bishop Adhemar, from the Provencal and southern Frankish host; among the northern Franks and Normans, Robert of Flanders, with Robert "Shortpants" of Normandy and Stephen of Blois, son and son-in-law respectively of William the Conqueror; Bohemond of Taranto, son of Robert Guiscard, and his nephew Tancred among the Normans from Sicily and Italy; and from the armies of the Rhineland and other German provinces, the brothers Godfrey of Bouillon and Baldwin of Boulogne. (There was also a peasant army led by Peter the Hermit. We won't bother keeping track of them - they didn't make it.) It took three years to get there, but they finally took Jerusalem by assault in July, 1099. Most of the crusaders returned home after the conquest, but many stayed on and settled down. They established western-style feudal states in the lands they had conquered: the Counties of Edessa and Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (with Godfrey of Bouillon as the first king). That was the end of the First Crusade, but just the beginning of the Crusading Era. |

Mediterranean area from an 11th c. world map, with east at top | |

|

The Second Crusade 1147-49 The First Crusade succeeded, despite a divided (sometimes feuding) command, poor supplies, and poorer planning, mostly because the Muslim powers in the region were just as divided and didn't cooperate either. But that changed. Starting in 1130 Zengi, Atabeg of Aleppo, began to establish a personal hegemony over the Muslim Middle East; in 1141 he conquered the crusader county of Edessa. In response, Pope Eugenius III declared another Crusade. The First Crusade had been an adventure, a religious quest with no realistic chance of success, so no kings bothered to go. This time, with an idea of the glory that could be won, two kings led national armies on crusade: Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. (Louis' queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and her ladies dressed up in costume armor and rode as Queen Panthesilea and her Amazons. Unfortunately for fans of The Lion in Winter, it does not appear that they actually rode bare-breasted.) When they reached the Holy Land the kings decided to attack Damascus, over the objections of the local crusader barons. Damascus was only a minor Muslim power, and was in fact an ally of the crusader states against the real threat, Nureddin (Zengi's son and successor) in Aleppo. But Damascus was in the Bible and Aleppo wasn't, so the Crusade rode for Damascus. They gave up after four days' fighting, when Nureddin's army showed up to rescue the city. The kings went home in 1149, having neither redeemed Edessa nor captured Damascus. (In what must have seemed even at the time as a desperate attempt at spin control, Geoffrey of Clairvaux wrote that although the Second Crusade "did not at all relieve the Holy Land, yet [it] could not be called unfortunate as it served to people heaven with martyrs.") | ||

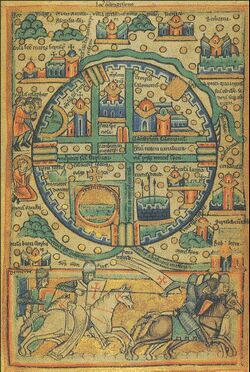

12th c. map of Jerusalem |

The Third Crusade 1189-92 The unification of Islam begun by Zengi and Nureddin was completed by Saladin, and in July 1187, at the battle of Hattin, he virtually wiped out the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Western Christendom responded with another Crusade, led by the three most powerful monarchs of the day: Frederick Barbarossa of Germany (drowned along the way, in Asia Minor), Philip Augustus of France (blind in one eye), and Richard the Lionheart of England. The Crusade was divided against itself from the beginning: Philip and Richard were enemies (or at best, rivals) back home; and the crusader kingdom - what was left of it - was torn between rival factions, one faction looking to Philip for support and the other to Richard. When Philip headed back home after the siege of Acre, and Conrad (one of the rival kings of Jerusalem) was assassinated, Richard was left in sole command; under his generalship the Third Crusade was able to reestablish the Kingdom, but only as a strip of coastline, without the city of Jerusalem itself. (So it's now usually called the Kingdom of Acre from this point, although the crusaders kept the title, Kingdom of Jerusalem.) Richard had conquered the island of Cyprus on his way east and established a crusader state there; this was the longest-lasting effect of the Third Crusade. | |

|

The Fourth Crusade 1202-04 Thibalt, Count of Champagne, wanted to get back to the spirit of the First Crusade, away from the royal and national rivalries that had plagued the Second and Third. His plan was endorsed by Pope Innocent III, and he and his friends started organizing a Crusade against Egypt. The sponsors had contracted with Venice for transport, but when they couldn't sell enough subscriptions and defaulted on their end of the deal, Venice took over the enterprise for its own commercial interests. Those interests favored Egypt (as a trading partner) but conflicted with the Byzantine Empire, so the Crusade was recast in terms of reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox churches, and attacked the Eastern Roman Empire. The crusaders took Constantinople in 1204 and sacked the city. They carved the empire up into western-style feudal territories (Venice got a plurality share) and elected Baldwin of Flanders as Emperor of Romania. The Byzantines reestablished an empire of sorts, which eventually reconquered Constantinople in 1261, but it never recovered its former power. | ||

|

The Fifth Crusade 1218-21 Like the Fourth Crusade, the Fifth set out to retake Jerusalem by way of Egypt. Why Egypt? Apparently, Richard the Lionheart had made some offhand comment during the Third Crusade that the Holy Land could never be defended against Egypt; and since the Lionheart said it, later Crusades based their strategy on it. The new Crusade met with some initial success (they took Damietta, on the eastern side of the Nile delta, in 1219) as the Muslims were distracted: Sultan Saphadin, Saladin's brother, was dying in Syria; his son al-Kamil was commanding in Egypt, but had to deal with conspiracies and attempted coups against him. After Saphadin died al-Kamil became Sultan, consolidated his power, and began to regroup against the Franks. He offered repeated concessions, including the city of Jerusalem, and later all of Palestine west of the Jordan, but the Crusaders refused to make any deal with the infidel. The papal legate Pelagius, self-appointed commander of the Crusade, was especially adamant on this point. Eventually the crusaders advanced too far towards Cairo and away from their base at Damietta, and were caught between the rising Nile and al-Kamil's reinforced army. They were crushed in battle, and made no gains for the crusader kingdom whatever. |

13th c. map of Jerusalem | |

|

The Sixth Crusade 1228-29 Now we meet one of the most fascinating and utterly unique characters of the Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, known to some as the Wonder of the World, and to others as the Antichrist. He had signed up to go on the Fifth Crusade but kept delaying, and finding excuses, and delaying some more, and in 1227 Pope Gregory IX excommunicated him for taking the cause too lightly. But Frederick was just biding his time and in 1228, with a claim to the crown of Jerusalem, he sailed on crusade. The Pope promptly excommunicated him again, for crusading while excommunicate. Frederick was a better diplomat than a military commander: he got Jerusalem conceded by treaty. He also got himself vilified for negotiating with the infidel instead of fighting. (Just to be fair, I should note that the Muslim leader was vilified by his side, too. This was the same Sultan al-Kamil who had tried to negotiate with the Fifth Crusade.) When Frederick entered Jerusalem for his coronation, the city was placed under Interdict for admitting a (double) excommunicate as its king. He was pelted with dung and garbage as he left Acre, and that was the Sixth Crusade. When the ten-year treaty ran out, neither side cared to renew it. | ||

the eastern Mediterranean from a 14th c. world map, with east at top |

The Seventh Crusade 1248-54 If the Sixth Crusade was led by the Antichrist, the Seventh Crusade was led by a saint: Louis IX of France, known to history as Saint Louis. Like Frederick, he went on crusade against papal wishes: the pope was busy with Italian-Imperial politics at the time, and he wanted Louis' help in Italy. But Louis was very sure of what God really wanted, and went ahead on his own. His Crusade was a naval invasion of Egypt (again, ruled by the Mamelukes now) - the largest naval action of the Crusades - coordinated with an overland attack by the Mongols under the Great Khan Guyuk. The naval invasion part of the plan succeeded. (The Mongols never showed up: they were busy elsewhere, and Guyuk had died, and they never really took the alliance seriously anyway.) But once they landed and took Damietta, the army was wiped out by dysentery. Louis and other leaders were captured, and released after their ransom was paid. | |

|

The Eighth Crusade 1270 16 years later, in response to renewed Mameluke attacks on the Kingdom of Acre, Louis undertook another Crusade. This time he attacked Tunis. (Why Tunis? Historians can only guess that Louis was supporting his brother's new kingdom in southern Italy and Sicily.) The army was wiped out by dysentery again; this time Louis succumbed, too. This was the last of the Crusades. They had lost focus and credibility, and when the Kingdom of Acre fell to the Mamelukes in 1291 the whole era was over. (The cannibalism? An incident during the First Crusade. Very distressing. Tell you about it some other time.) If ever you need help remembering the sequence of the Crusades, there's a Handy Mnemonic Verse. But actually, all this is just preamble to what I really want to talk about: the Crusader lands of Outremer. ("Outremer" is French for "overseas," and was the collective term for the various crusader states of the Levant.)

The Crusader States Of the realms of Outremer, the foremost was of course the Kingdom of Jerusalem (later the Kingdom of Acre). When the First Crusade took Jerusalem, the commanding lords naturally inclined toward setting up a typical feudal realm, ruled by a typical feudal leader - i.e., one of them. They ended up choosing Godfrey of Bouillon, partly because of his undoubted piety, but mostly because he was the least ambitious. Godfrey refused to be called King, saying he would not take that title in the city where Jesus had been crowned with thorns; instead he called himself "Defender of the Holy Sepulchre." (His successors however, beginning with his brother Baldwin, had no problem with the title "King.") But the King of Jerusalem was not an absolute ruler. The affairs of the kingdom were mostly run by the High Court, a council made up of the ranking peers of the realm, clergy of the major cities, and officers of the kingdom (the constable, the seneschal, etc.). The High Court made law and decided policy for the kingdom, advised the king and...elected the king. (Shocking!) Oh, the new king was often chosen from the family of the previous king, or was quickly betrothed to a princess of the royal family, to give a sense of continuity, but the structure of the Kingdom never got far from the structure of the Crusade - no overall commander. Besides Jerusalem, here's a word or two about the other lands of Outremer: | ||

|

County of Edessa - This was the first crusader state won (by Baldwin of Boulogne, along the way on the First Crusade), and the first one lost (launching the Second Crusade). The first two counts became kings of Jerusalem, as Baldwin I and Baldwin II. | |

|

Principality of Antioch - Bohemond of Taranto took the city (by treachery) during the First Crusade, took the title of Prince, and stopped there. The princes of Antioch stayed independent of the Kingdom of Jerusalem - for instance, they were conspicuously neutral during the Third Crusade. | |

|

County of Tripoli - Conquered by Raymond of Toulouse after the First Crusade (sort of Crusade 1.5). Though he had said he didn't want the honor, Raymond may rather have expected to be chosen as first king of Jerusalem, and this was his consolation prize to himself. | |

|

Kingdom of Cyprus - Established during the Third Crusade, it was always closely linked with the Kingdom of Acre but never united with it. (For instance, when King Amalric I of Cyprus became Amalric II of Jerusalem, he kept his two governments separate.) The kings of Cyprus were more hereditary, and swore fealty to the Holy Roman Emperor. | |

|

Latin Empire of Constantinople - Legacy of the Fourth Crusade, it never really connected with the other crusader states. The land was divided up, with one-quarter going to the Emperor directly, three-eighths to other crusader lords, and three-eights to Venice; the Emperor was elected, with Venice getting 6 of the 12 electoral votes. (All in all, Venice got a pretty good return on its investment.) | |

|

The Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem/Acre lasted just under 200 years - from a

modern perspective it seems like a dead end, well worth ignoring. Any

importance attached to the whole movement is usually retrospective, put in

terms of later history: established trade with the East, a taste for

spices, the first massacres of Jews in Europe, and so forth. All true

enough, but (in keeping with the tenor of these essays) I want to emphasize

more the way that, for two centuries in the core of our period, the lands

of Outremer were important in the medieval mind, and the Crusades were not

exceptional but were part of What Was Going On.

At least eight crowned heads of England, France, Germany, and Hungary went on Crusade; many others considered it, or contributed money, or at least bought into the rhetoric. That the effect of the Crusades on the Eastern Roman Empire was drastic is pretty unequivocal, and the effect on Turkish Islam was just as great (though in the opposite direction). In the field of literature, the "eyewitness chronicle" and the narrative prose history were genres that evolved in the campaigns of Outremer and came back to Europe. The institution of the Crusade was applied to very real effect elsewhere than the Holy Land - consider the Albigensian Crusade and the conquest of Languedoc. And anything that gets the Holy Roman Emperor excommunicated twice, without being re-communicated in between, must have been significant at the time. And what does it all mean for us? From time to time the idea of choosing SCA kings by election (rather than combat) gets floated, and one of the perennial counter-arguments is that election would somehow go against the "medieval ideal of kingship." It is interesting therefore to note that the kings of Jerusalem, along with other rulers who were seen in period as being ideal or universal in nature - the Holy Roman Emperor, the Pope - were in fact elected. Of course, I don't deny in any way the plain truth that most medieval crowns were hereditary, not elected - then again, they weren't won in single combat, either. Speaking of which I also note that, although the MSR named their fictive kingdom after one that historically was elected (Acre), and although the immediate cause of their splitting off from the SCA was a Crown Tourney, their procedure for choosing kings is even more artificially combat-driven than the SCA's. Lastly, and in light of the baronial election issue of A.S. 30, notice also that these "ideal" elected rulers were all elected by a council or committee: the High Court of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the imperial electors of the Holy Roman Empire, the College of Cardinals. In fact, of these the Great Council of Carolingia is really rather similar to the High Court of Jerusalem as an institution. Further Reading Whole libraries have been written on the history of the Crusades; here, I'll just recommend one good book from the main stream, and a few perhaps less typical. The mainstream text is A History of the Crusades, by Steven Runciman, in three volumes, well-written and easily readable (highly recommended by wargame designer Richard Berg, too). For less conventional but still interesting takes, may I suggest: The Alexiad, Anna Comnena's biography of the emperor Alexius, which includes the First Crusade from the Byzantine point of view; James Michener's epic novel of Judaism, The Source, which has a chapter on the First Crusade and the crusaders who settled down to occupy, and a beautiful little bit contrasting the crusading styles of Frederick II and Louis IX; and Crusades, a mini-series (and associated book) that Terry Jones (of Monty Python fame) did for cable TV - very appealing for Creative Anachronists, as he dresses up in garb and armor of different periods in the crusading era, and tries hiking over the highlands of Anatolia in thin slippers, or assauting Jaffa in armor, hip-deep in the surf. Check out his exposition of the Washerwoman Question as well. Across the aisle in Fiction, I highly recommend a pair of historical novels, Knights of Dark Renown and Kings of Vain Intent, by Graham Shelby. The first is set in the Kingdom of Jerusalem just before Hattin, the second during the Third Crusade. The factions within the crusader kingdom are rather starkly drawn (one side Good, other side Bad) but otherwise the writing is very good, the characters very engaging. Warning: the second book (Kings) is incredibly depressing. | ||

|

| ||

|

text copyright 1997 by Caleb Hanson (e-mail) all maps adapted from Jim Siebold's magnificent Cartographic Images website | ||

Home |

Usage |

Forums |

Articles |

Patterns |

Graphics |

Extras |

Contact Us

|